Alan Wake 2 surprised us in so many ways – how different it was from its predecessor, how much Saga Anderson added to the Alan Wake story, the way Alan Wake 2 really tied all the Remedy games together. But the biggest surprise of all begins with two words that take up almost the entire page:

we read

WARNING: This is your chance to get out of here before I spoil one of the craziest, weirdest, and best gameplay moments in Alan Wake 2.

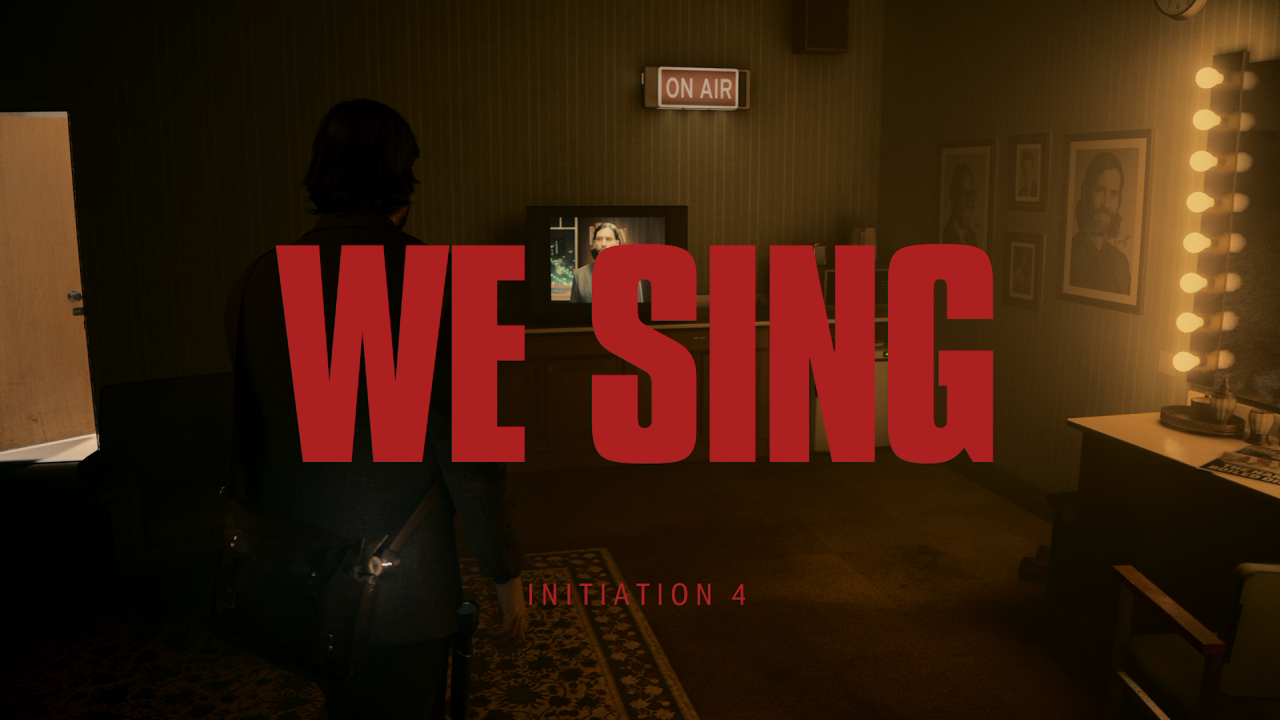

Alan Wick is stuck in a loop. The dark place wants to keep him trapped and confused so that it can use his creativity to manifest itself in the real world. Time and time again, Vic found himself without logic or explanation in the green room of a late-night talk show called In Between with Mr. Door finds. Mr. Door knows why Alan is there – to talk about his new book, The Return, which Alan didn’t write. However, in one loop, Mr. Door informs Alan that they need to talk about his journey so far, and it’s best to do it through song.

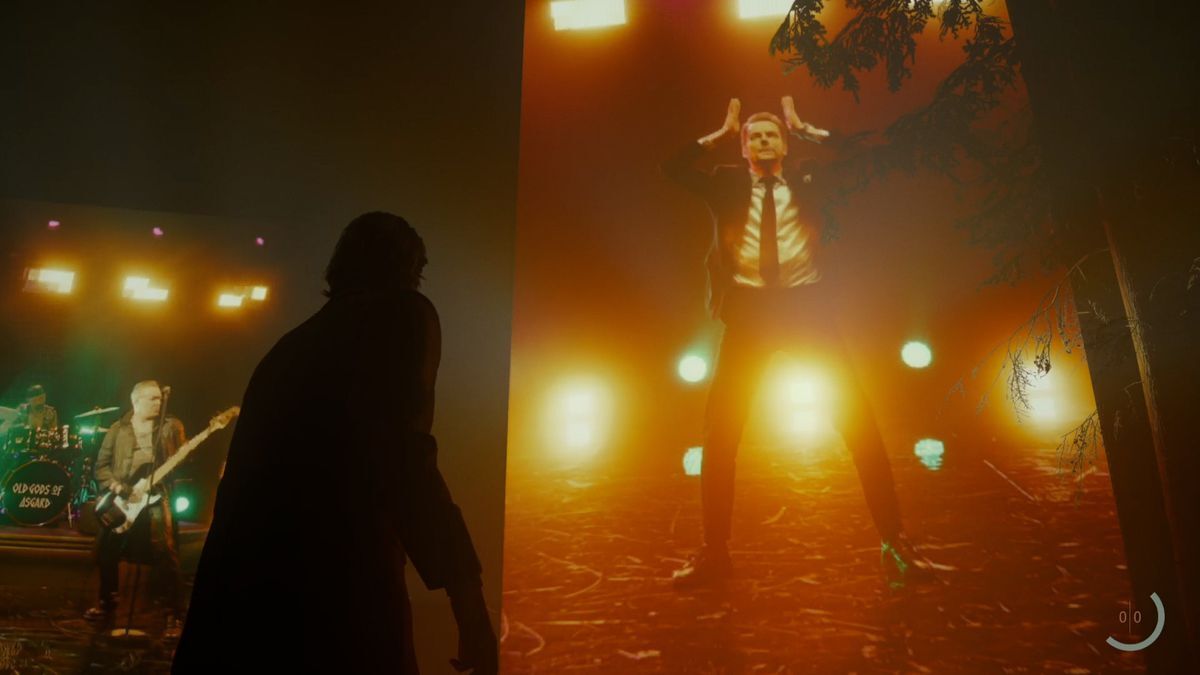

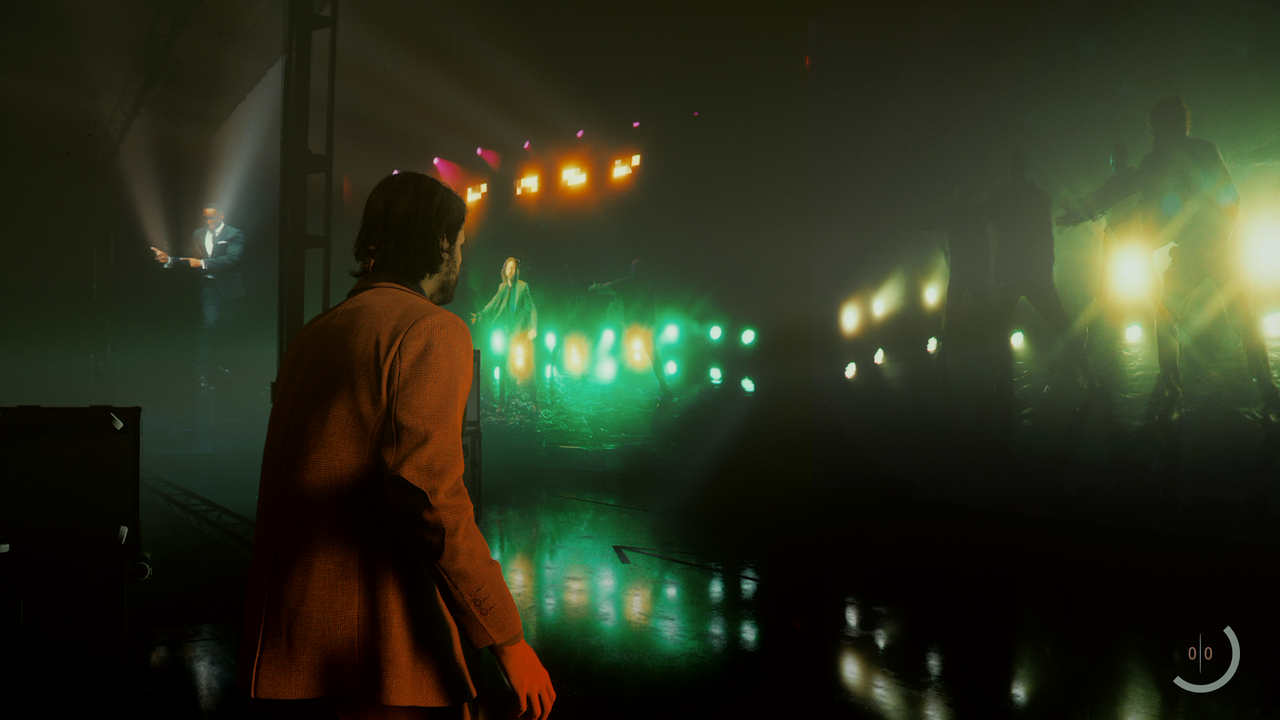

What follows is the most fun I’ve had playing a narrative video game in a long time. Metanarratives—a story about a story, basically—are nothing new for Alan Wick. This is his everything. However, here it becomes literal and performative in a way it never has before. Huge LED screens with live videos descend from above. In front of you, a screen showing Mr. Door (David Harwood), the fictional host of a talk show that seems to exist only in the dark, beckons you forward. The reflective, black flooring ahead is interrupted only by gaff tape to guide you as you approach the door that stands in the middle of the room and begins your wild journey through Alan’s life in musical form.

The song itself is very catchy and equally true. It is performed by The Old Gods of Asgard, the name used by the Finnish rock band Poets of the Fall, who have appeared in almost every Remedy game since 2003. As Alan Wick on screen reads his own perspective on the story (much to the confusion of the Alan Wick we actually control), with vocals by Alan Wick’s voice (Matthew Porta) and face (Ilka Wiley). It’s a basic musical-style musical, with very literal lyrics – the characters speak their feelings and thoughts out loud in a way that a real person never would. The Old Gods of Asgard gave this song a 1970s and 1980s ballad metal backing as well as their own vocal track.

Everything that happens here is meaningful, not just to us as people playing Vic’s story. wake himself upAnd that makes it all the more compelling and immersive, even when the game takes off the clothes of a video game. In his pre-Dark presence, Vic used to—and hated—being interviewed on late-night shows, with Mr. Door structuring the interview with his quotes. The members of Old Gods and their music played an important role in starting Wake’s journey. It is personal to both the character and the player.

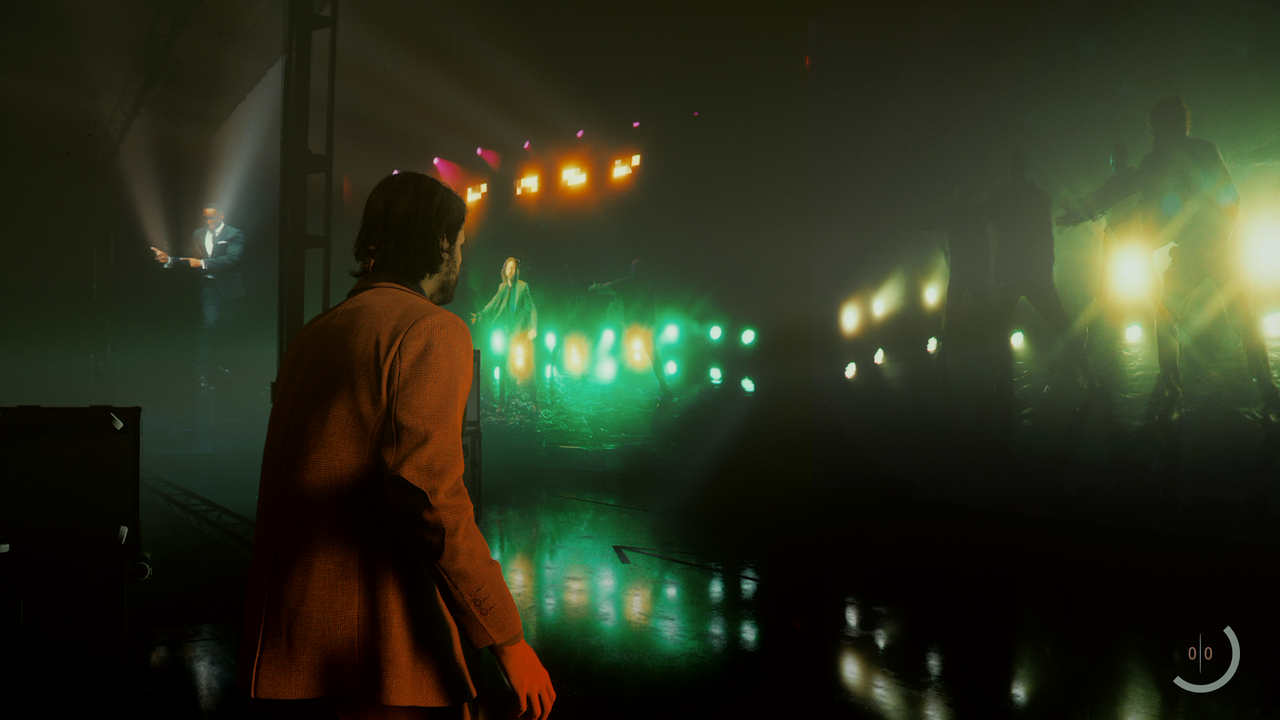

The pages above you are all directly literal and hypertext, as only Remedy really does. Alan, Mr. Door, and the Old Gods are joined by a fourth figure – Lake Sam. The presence of Sam Lake in this sequence means many things. Lake is Remedy’s creative director and has played all of its games from inception to release, as director, director, writer, co-writer, and sometimes even a character. In Alan Wick 2, Leake takes on the visual role of Alex Casey (while James McCaffrey provides his voice – similar to how Wick’s likeness and voice are played by two different actors), an FBI agent whose name just happens to be Same with Hard Boiled Man. New York detective in Alan Wick’s books, and one who is fully aware of this connection. Lake also provided the face for the original Max Payne, and the over-the-top grimace remains a meme among gamers to this day.

The “real” Alex Casey, Saga’s partner, doesn’t play a significant role in Alan Wake 2 compared to Alan himself and Saga. It does not make sense for Only Alex Casey for appearing in this sequence. But in the metatextual nature of the Alan Wick story, it makes sense for Sam Lake – the creator of Alan Wick – and Alex Casey – the creation of Alan Wick – to appear. As Lake dances with a goofy grin on his face, he seems to be taunting Alan from both sides of Alan’s reality, just as the dark presence both controls and is controlled by Vic. I love the way this not only connects Remedy’s various projects together, but also connects Leek to his own writing. I feel like I can see some of the struggles Lake and his team went through putting these stories together.

The detached structure of Alan Wake 2, with Wake exploring a looped reality and experiencing the story through old CRT televisions, comes into play here as well. As the song pauses, a confused Vic finds himself standing in front of the television in a black void. Looking at it, he was drawn back into the song. It partially hides the loading screen, but it’s not just a static screen that tells you “just wait a second and we’ll have more story for you.” Instead, it reminds us of the story-within-a-story loop that Vic is stuck in. We stared at one TV to get here and now we’re reviewing another. Is this real? Was the previous location real? It cleverly uses these transitions to put us in Vic’s own mind.

This game takes our interactive scene to concepts like clicker and events from the first game. However, in all these cases, there is Never A question that you are in a collection. You are not in a real place per se, but inside a creation of Vic’s mind designed to disrupt his perception of reality. Even when you find a place with brick walls, neon signs and a taxi cab, you’re quickly drawn to the back of the set, with its wooden back and supports where the props are kept. When you’re presented with a copy of Allen’s writers’ room and a flare gun, the backdrop goes up on the wires. It’s all mansion On one page, Lake/Casey/Payne beckons you to continue.

Enemies emerge from the darkness to attack Vic, and this is the first time in AW2 that he’s fought enemies that didn’t start out as shadow semblances. These enemies are more like the ones Saga – and Alan himself in the original Alan Wake – fought. They act not like manifestations of the dark presence, but like people taken in the real world who are possessed by the dark presence. Apart from Alan, these are the only other physical beings in the sequence, and this change makes them look a bit like actors playing enemies, rather than just enemies, deepening the sense that everyone These are a performance and interactive theater designed for a special person

After some intense fighting, you find another TV and finally get out. That is, until you see one of the numerous perspectives throughout the game. Usually, these show a memory of Alex Casey’s ghost as Alan investigates the murders in the scope of his manuscript. This time, however, the surface around you rises once more on the cables to reveal a screen of Vic dancing impatiently and singing a song in a hall that repeats the lyrics “You gotta understand … to finish this song”. It all ends with Alan waking up on the set of Mr. Door, where they perform the final epic musical sequence with dancing and an epic guitar solo, all in live action. Vic sits down, tired, but clearly impressed. Who is he influenced by? With himself, with Mr. Scratch, with Sam Lake? It has the potential to be all self-congratulatory, but Vic specifically responds to that, rather than the game just telling us what to think.

Rather than trying to be immersive, this sequence commands attention as a literal set piece. We often use this term – set piece – to describe major events in games. It works here too, but those moments were never chunks on a set, They were all meant to be taken as facts—Up to this reality bending performance. This game combines a lot of things about the Alan Wake and Remedy games.

Wick’s metanarrative is on display here, but so is Remedy’s ongoing experience in storytelling. Max Payne used audio comic book panels to tell his story. Alan Wick’s American Nightmare cast Ilkka Wiley as Wick and Mr. Scratch in the live-action series. Quantum Break aired all the TV episodes. Jesse Faden spoke to us directly from Control not as a viewer but as the source of his special powers. While learning about the history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, he encountered ghostly visions presented in abstract live action. Max Payne 2 ended with the song Poets of the Fall, Alan Wake an original stage piece – also on stage, by the way, but much less metatextual – backed by an Old Gods of Asgard song and composed by the Old Gods. In control, he is shown to have supernatural powers. Here, they’re literally part of the story, not just as the old hard rockers Saga meets, but as their younger selves, still active as a band.

All of this feels like a bonus to the player, providing the many dangling pieces of Vic’s story and tying them together in a way that is self-referential but self-aware. There’s never a moment where I wonder if Remedy knows what he’s doing with this sequence. Most of the time, the player is just the consumer and the audience, but here Remedy includes us in the process, remember we were here for it all. It’s always fun and surprising, but it also serves as history for Alan Wake and Remedy Games itself – and it’s meta – and metal–like hell.